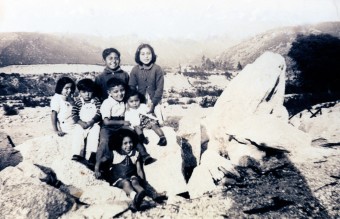

I grew up in New England with a forest outside my back door, but my grandparents grew up in the high desert above San Bernardino, Calif. An old family photo shows my grandmother at 9 years old, surrounded by her siblings and friends, perched atop a cluster of rocks with the scrub and sand of Cajon Pass behind them, grinning in the sun.

When they were grown and married, my grandparents set up house in the suburbs east of LA, but my mom remembers driving up to Big Bear in the San Bernardino National Forest every New Year’s Day, where they would play in the snow among the mountain pines (though like the true LA County girl that she was, my mom also remembers quickly retreating to the warmth of the car). My dad’s character was formed in nearby Orange County, but as a child, digging through boxes in the basement, I remember coming across the heavy old external frame pack that he carried through the redwoods when he lived in the Bay Area for college.

So you could say that being outside, exploring nature in an unstructured way, runs in my family. As a kid I remember slathering my bare legs with mud so I could feel it dry and crack in the sun, overturning rocks and logs to catch salamanders and feel them dash madly inside my cupped hands, and tramping through the woods unsupervised until the sun went down.

It’s little wonder, then, that when I turned 18 I found myself drawn to a place like Oregon, with its wild and scenic rivers, untrammeled wildernesses, and snow-capped mountains on the horizon. I love living in Portland, and as I move about the city I love being able to look out on a clear day and see wilderness—when I look at Mt. Hood to the east I can picture last summer’s hike to Ramona Falls, and when I see Mt. St. Helens to the north I can put myself back on Johnston Ridge, gazing into the volcano’s crater.

We live in the mountains’ backyard, but so many young people in Portland, Bend, Salem, don’t see wilderness when they look to the horizon. They’ve never been there. They’re growing up in one of the greenest regions in the world but they may struggle to care about the environment or about conservation, because without access to wild open places, those are just words. Without the opportunity to explore the outdoors with all their senses, and to not be told what time to come inside, they’ll never feel the intense connection that I feel, that sense of coming home when I breathe in the mountain air and listen to the wind in the trees.

But we’re working to change that. This year for the first time Opal Creek Ancient Forest Center is offering full scholarships to our summer backpacking programs, Opal Creek Expeditions, to young people who would otherwise never have the chance to spend a week traveling through the backcountry of our old-growth forests. I remember my first backpacking trip at age 17 so clearly. I remember how hard it was to keep pushing myself forward, to find energy and determination I didn’t know I had—and I wish that life-changing experience for every single one of our scholarship recipients this summer.

This scholarship program is so important, because the natural world is changing, and it’s changing fast. These changes are going to affect all of us, but overwhelmingly they’re going to affect those of us with the fewest options and the least-heard voices on the world stage. Those mountains on the horizon belong to all of us, no matter where our parents came from or whether as children we played in the dirt or on asphalt. And someday soon those mountains are going to need us, and we’re going to need as many voices crying out to defend them as we can get.